Joe Caldwell is the 'Curt Flood' of professional basketball. He was the pioneering father of free agency for the National Basketball Association (N.B.A.) players. Unfortunately, an unprecedented scenario of chicanery, betrayal and collusion victimized him throughout his life. This type of situation was never before seen on the American sports scene. Joe Caldwell is the 'Curt Flood' of professional basketball. He was the pioneering father of free agency for the National Basketball Association (N.B.A.) players. Unfortunately, an unprecedented scenario of chicanery, betrayal and collusion victimized him throughout his life. This type of situation was never before seen on the American sports scene.

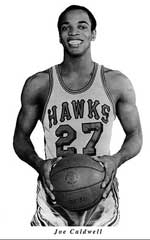

In 1964, Joe Caldwell had it all. He finished a standout basketball career at Arizona State University as an All-American, and he later that summer made the 12-man U.S. Olympic team. At six-foot-five-inches, he could jump like a kangaroo and was nick-named "Pogo Joe." All of this was not bad for an innocent 21-year-old who was raised in poverty and never picked up a basketball until he was in junior high school. He played his way out of the tough Watts ghetto in Los Angeles, California into the world of professional sports.

Caldwell was the first player selected for the U.S. Olympic basketball team out of 100 invited hopefuls who tried-out in Lexington, Kentucky. Some of the others who tried-out like Cazzie Russell, Willis Reed and Dave Stallworth were highly publicized. Ironically, they did not make the squad. The team was led by Lucious Jackson and defended by Joe Caldwell who scored 17 and 14 points during the game, respectively. The Americans defeated the Russians with a score of 83 to 59 points and captured the gold medal that year.

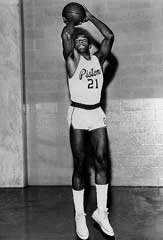

After Joe victoriously returned from the Olympics, the Detroit Pistons chose Caldwell as their number one draft-pick. It appeared like Joe's professional career was bright and he was headed for stardom. He made the All-Rookie team and the All-Defense team during that season. His athletic ability was so impressive that the following year he received a $17,000 offer from the Los Angeles Rams. This amount was $3,000 more than the Pistons were paying him. After Joe victoriously returned from the Olympics, the Detroit Pistons chose Caldwell as their number one draft-pick. It appeared like Joe's professional career was bright and he was headed for stardom. He made the All-Rookie team and the All-Defense team during that season. His athletic ability was so impressive that the following year he received a $17,000 offer from the Los Angeles Rams. This amount was $3,000 more than the Pistons were paying him.

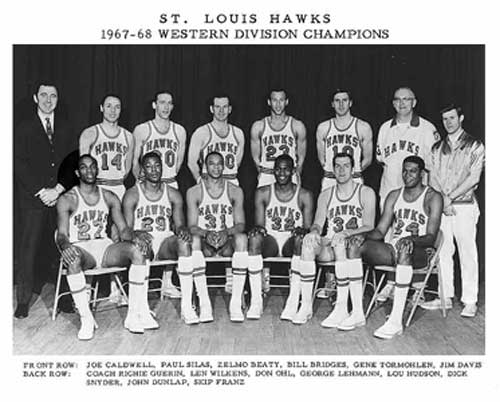

Nonetheless in 1966, the Pistons traded Caldwell to the St. Louis Hawks who were coached by Richie Guerin. Joe joined a strong team that included Lou Hudson, Lenny Wilkens, Zelmo Beatty and Bill Bridges. Even though the team had good camaraderie, the player-management relationship was a rocky one at best. While playing with Hawks, Caldwell had his first bad experiences with management. These were the experiences that would haunt him the rest of his career.

Back in the infancy of the N.B.A., there were only nine teams in the league, the games were televised only once a week, and the players were not allowed to have agent representation. This is a far cry from the N.B.A. that exists today.

Therefore, Caldwell had to deal with the Hawks' owner, Ben Kerner, himself. Kerner had the reputation of being the league's cheapest owner. Nevertheless, Caldwell negotiated a two-year contract with him that paid $27,000 the first year, $30,000 the second year, and included a $20,000 home loan. The deal was not as sweet as it seemed. Caldwell never got the loan, but the contract was signed. Kerner never had the intention of loaning Caldwell any money to buy a new home. He just wanted him to sign the contract.

The Hawks were one of the top teams during the 1967-1968 season. They finished the season with a 56 to 26 game lead and were destined to go to the playoffs. Unfortunately, Kerner had other ideas for the team. He was secretly negotiating to sell them to a group of investors in Atlanta, Georgia. This was a devastating surprise to everyone on the team including Caldwell.

Kerner was a prideful and paranoid individual. He was always more concerned about himself than about the team's welfare. Kerner's idea was to sell the team to the investment group and relocate it to St. Louis, Missouri or Atlanta, Georgia. The first part of his plan was to undermine the team's playoff chances. In the opening playoff series against the San Francisco Warriors, Kerner ordered Guerin not to play Caldwell. This crucial decision set the stage for the Warriors to win the best of seven with a score of four to two (4-2) games. Ultimately, providing Kerner with justification to sell the team. He had an initial investment of $500 which gave him more than a $3.5 million windfall.

Since the players were still not allowed to secure the services of an agent, Caldwell turned to a hard-nosed Los Angeles negotiator named Marshall Boyer. He specialized in real estate transactions, however he took an interest in Caldwell. "How much are you making?" he asked.

"I'm only making $30,000 a year, despite being on the All-Star team," answered Caldwell. "Managements' lawyers keep beating me down."

"How much would you like to make?" "I'd like to get $80,000 a year!"

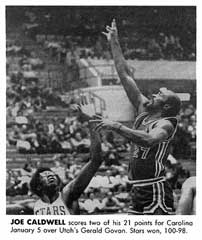

Boyer was able to get Caldwell $60,000. This newly negotiated amount was double what Caldwell was paid prior to getting Boyer involved. During the 1969-1970 season, a much more content and happy Caldwell made the All-Star team again. He averaged 21.1 points a game. He went from "super sub" to "superstar" at the age of 26. The Hawks also went to the playoffs again. Unfortunately, they never got the chance to enjoy it. Guerin and Caldwell both overheard two men taking in the breezeway of the Georgia Tech Coliseum. One of the men was Walter Kennedy, the N.B.A. commissioner, and the other was Mendy Rudolph, one of the league's top officials. Boyer was able to get Caldwell $60,000. This newly negotiated amount was double what Caldwell was paid prior to getting Boyer involved. During the 1969-1970 season, a much more content and happy Caldwell made the All-Star team again. He averaged 21.1 points a game. He went from "super sub" to "superstar" at the age of 26. The Hawks also went to the playoffs again. Unfortunately, they never got the chance to enjoy it. Guerin and Caldwell both overheard two men taking in the breezeway of the Georgia Tech Coliseum. One of the men was Walter Kennedy, the N.B.A. commissioner, and the other was Mendy Rudolph, one of the league's top officials.

"Just look at this, only 7,200 people in the place," snapped Kennedy. "We have to have more than this for the playoffs."

Guerin was infuriated by what he heard. He realized they were conspiring to try to knock the Hawks out of the playoffs again. This was the most frustrating situation because he was powerless. There was nothing he could do to stop the conspiracy. In the first playoff game against the Los Angeles Lakers, 34 fouls were called against the Hawks. The pattern was set. Guerin was furious.

"A lot of blood will be spilled on the floor if the officials continue to call little, bitty fouls," fumed Guerin to the media. Kennedy got tired of his comments and fined him $1,000 for "comments that were detrimental to basketball."

The Lakers swept the Hawks to a four to zero (4-0) victory. During the final game in Los Angeles, Jerry West went to the free throw line 21 times. In four games, he went a total of 57 times! It was completely unbelievable.

During the 1970-1971 season, Caldwell was voted the fans' favorite Hawk for the second year in a row. This recognition gave Boyer the negotiating power he needed. He was looking into a two-year contract for $2 million. In that same year, Pistol Pete Maravich, the all time leading scorer in college basketball, signed a five-year $1.9 million contract. It was the largest contract in professional basketball and in all of professional sports at the time. During the 1970-1971 season, Caldwell was voted the fans' favorite Hawk for the second year in a row. This recognition gave Boyer the negotiating power he needed. He was looking into a two-year contract for $2 million. In that same year, Pistol Pete Maravich, the all time leading scorer in college basketball, signed a five-year $1.9 million contract. It was the largest contract in professional basketball and in all of professional sports at the time.

Tom Cousins, one of the Hawks' owners, and Caldwell agreed upon a five-year $1.875 million contract with a handshake. Later that day, Cousins claimed to Boyer that he did not offer Caldwell that amount of money. This disgusted Caldwell. It made him feel totally betrayed by the game he loved and he decided to quit all together.

Caldwell went to work for, R.E. Finley, one of the biggest carpeting manufacturers in the southern United States. The agreement was that Caldwell would be paid 15 percent of the yearly profits. This was more money than he made playing basketball for the Hawks. Ironically, basketball was not too far away. Tedd Munchak, the owner of the American Basketball Association (A.B.A.) expansion team the Carolina Cougars, got word to Caldwell that he would pay him what he wanted to play for him.

Boyer negotiated a rock-ribbed contract for Caldwell with an irrevocable guarantee. In other words, this guarantee meant that under no circumstances could the contract be amended by any party and could never be changed by a court of law. Unfortunately, there was a legal roadblock. The N.B.A. had a "reserve clause" in their contract. This type of clause is like a security blanket that made sure the power rested with the management and not with the players. In this case, it specified that any player who jumped from one league to another would have to be out of the game for one full year. The Hawks served Caldwell with an injunction, but it failed. Boyer negotiated a rock-ribbed contract for Caldwell with an irrevocable guarantee. In other words, this guarantee meant that under no circumstances could the contract be amended by any party and could never be changed by a court of law. Unfortunately, there was a legal roadblock. The N.B.A. had a "reserve clause" in their contract. This type of clause is like a security blanket that made sure the power rested with the management and not with the players. In this case, it specified that any player who jumped from one league to another would have to be out of the game for one full year. The Hawks served Caldwell with an injunction, but it failed.

In January 1971, Judge Edwin Stanley of the Federal District Court ruled in Caldwell's favor. It was a landmark decision. He contended that the Hawks had violated the N.B.A. "reserve clause" by offering Caldwell less than 75 percent of his previous contract. He concluded that this violation allowed Caldwell to become a free agent and was eligible to sign with another team. Caldwell became the first N.B.A. player in the history of the sport to successfully jump leagues without having to sit out a year. The N.B.A. never forgave him for this ruling.

"I couldn't pass it up," explained Caldwell. "I didn't want to end up like Joe Louis. I was named for him. My agent didn't want that to happen to me."

Boyer pressed Munchak for the pension contract. At the end of the 1971-1972 season, he still had not received it. During the break of the All-Star game, Munchak flew Caldwell to a meeting in his Atlanta mansion. When Caldwell arrived, he was surprised to be greeted by Lou Hudson, Walt Hazzard and Bill Bridges.

"Joe, we want you to come back to the Hawks," exclaimed Bridges. Caldwell was stunned. "Joe, we want you to jump back to the N.B.A.," revealed Munchak. Caldwell was beside himself.

"If you don't want me to play for you, trade me and I'll be alright with the trade," offered Caldwell. I just can't jump back to the N.B.A. after all I've been through. We have a deal."

"Joe, I can't trade you to the N.B.A.," disclosed Munchak. "They won't take your pension. Nobody will touch it."

The pension, which cost Munchak $600 per month for each year of service as basketball player, was the heart of the issue. Munchak believed that if he could get Caldwell to jump leagues, then he would be off the hook and wouldn't have to fund his pension any longer. Caldwell turned him down.

The rest of that season, Caldwell was constantly harassed both on and off the court. During a game against the Utah Stars, one of his own teammates, George Lehman, kept calling him "nigger" in front of the opposing team. After Caldwell heard it for the fifth time, he challenged Lehman to a fight at halftime. They went at it and Caldwell was later fined $500 by management, and Lehman didn't have to pay a dollar. The rest of that season, Caldwell was constantly harassed both on and off the court. During a game against the Utah Stars, one of his own teammates, George Lehman, kept calling him "nigger" in front of the opposing team. After Caldwell heard it for the fifth time, he challenged Lehman to a fight at halftime. They went at it and Caldwell was later fined $500 by management, and Lehman didn't have to pay a dollar.

The secretary of Carl Scheer, the General Manager of the team, even tried to bait him.

"Joe, Mr. Munchak is considering making you the coach of the Cougars," she smiled. "How do you feel about it?"

"I have a few good years left in me as a player…if I was to get into coaching, it would be after I retired," answered Caldwell.

It was another ploy to get rid of the pension contract. When this strategy also failed, the Cougars offered Caldwell a new contract for more money. It came with a condition. He would have to drop the pension plan. Caldwell refused to give it up.

Caldwell suddenly suffered further indignities just outside of the Cougars' den. He received four speeding tickets in a row. Oddly enough, he was driving five miles under the speed limit each time and still got the tickets. Finally, the violations resulted in Caldwell losing his driver's license for six months.

In 1972, Larry Brown became the Cougars third coach in two years and wanted Caldwell to play for him. At first, Caldwell was looking forward to playing for Brown because they were teammates during the 1964 Olympics. Caldwell quickly discovered that things had changed. His old teammate was in management. In 1972, Larry Brown became the Cougars third coach in two years and wanted Caldwell to play for him. At first, Caldwell was looking forward to playing for Brown because they were teammates during the 1964 Olympics. Caldwell quickly discovered that things had changed. His old teammate was in management.

The Cougars' management staff began to isolate Caldwell from his teammates, and Brown began to tell the other players that Caldwell wouldn't be with the team much longer. Surprisingly enough, he played the entire season opposite Billy Cunningham, the other forward, and won the Eastern Division with a 57-27 record.

The Cougars defeated the New York Nets with a four-game to one-game victory (4-1) in the semi-finals. They were confident that they would beat the Kentucky Colonels in the A.B.A. championship finals. Before the game even started, Munchak made his move to destroy the dream. On April 11, 1973, a U.S. Marshal walked unannounced into the Cougars' dressing room at 6:15 p.m.

"Is there a Joe Caldwell present?" he shouted.

"What's up," greeted Joe.

"I have a summons for you Mr. Caldwell," stated the marshal. "The summons was being presented to Joe Caldwell, on the behalf of Munchak of Delaware, for doing business in North Carolina with the Carolina Cougars."

Twenty-seven years later, the situation has not resolved for Joe Caldwell. The former All-Star, All-Team, All-Defense, fan favorite, superstar, and Olympic Gold winning professional basketball player waits to be heard and properly acknowledged by the National Basketball Association. Does he deserve to be reinstated into the sport he loves? You decide…

You can read more about the deception, betrayal and collusion that victimized him throughout his life in his soon to be released autobiography.

Works Cited/Referenced:

"Caldwell's contract is valid and irrevocable. A court order can't be revoked." Prentiss Yancey Former ABAP attorney (April 2002, Atlanta)

"Joe Caldwell has been blackballed." Julius Erving Hall of Famer (TNT, May 2, 2002)

"I feel he's been wronged." Jo Jo White Hall of Famer

"Foul!"

Mel Davis Executive Director NBA Retired Players Assn.

"Joe paid-the price." Lou Hudson Ex-Atlanta teammate

WHAT THEY SAID...

"He had one of the all-time great bodies in pro-basketball, a lethal combination of power and speed."

Al Attles

"Nobody could outrun or out jump Joe. He is the original Pogo." Archie Clark

"When Joe guarded me, he gave me fits. Toughest defender I ever faced. He was 6-5 and could jump out of the gym."

Dave Bing

"I would have loved to have been more exciting as a player, to have been someone like Joe Caldwell."

Jerry West

"Joe was the most exciting player I've ever played with and coached. Him leaving our team for the ABA was really the demise of our team in Atlanta, not Pete Maravich."

Richie Guerin

"He probably jumped higher than anyone I ever remember shooting a jump shot. He was unbelievably successful because of his athleticism. He was an incredible athlete, ahead of his time."

Rick Barry

"Joe was one of the two best defenders I ever played against."

Walt Frazier

"Without him, we had no chance of winning. Joe Caldwell and Pete Maravich were the only two players I'd pay to see play."

Gene Tormohlen

"Very athletic, very fast, very tough defensively. He was strong, could play forward or guard and had tremendous jumping ability."

Red Holzman

"I didn't know how he was, but Carl Scheer said we have to have a guy like him." Tedd Munchak

"Joe Caldwell should be in the Hall of Fame. One of the greatest players who ever lived."

Marty Blake - NBA scouting director |